In his essay "Studying the Fairy Tale," Dundes warns about the tendency to only study fairy tales from the brothers Grimm and Perrault. True folktales are orally circulated, therefore any written tales are "only a pale and inadequate reflection of what was originally an oral performance...from this folkloristic perspective, one cannot possibly read fairy tales; one can only hear them."

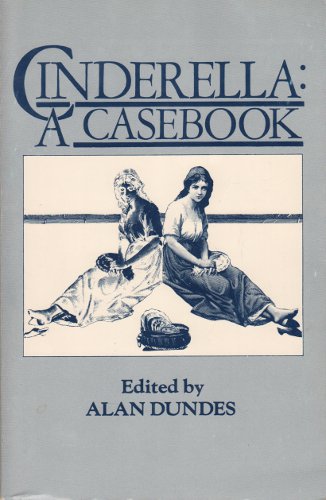

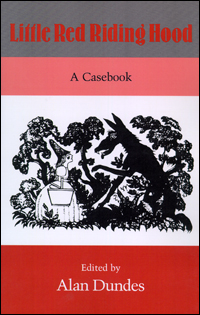

Sure, there are differences between fairy tales being told and being written and read, but written tales allow us to preserve and spread them much easier. However, when it comes to the traditional fairy tale collections, we have tales that were manipulated and changed, multiple variations spliced together, or chunks added or removed just to please the audience. The issue is that many scholars tend to only analyze these most popular versions of fairy tales, ignoring the folk variants that exist. Thus people too often come to the wrong conclusions when focusing on details that aren't essential to the tale type itself-such as pumpkins and glass slippers in Cinderella, or analyzing the significance of the color red in Riding Hood's cloak.

Herbert Cole

To really understand a tale, its history, how it is shaped by culture and how it shapes culture, you really have to look at multiple versions. However, a major issue is availability. Dundes suggests that you "simply apply" to one of the archives that contain vast collections of unpublished folktales; the majority of tales collected by folklorists over the last centuries remain unpublished (at least in 1986, when he wrote this essay). However, that doesn't really seem feasible unless you're a very serious folklore student, not a blogger doing this as a hobby, or someone mildly interested in learning more about fairy tales.

Fortunately for us, there's the Surlalune book series which collects variants from around the world, as well as the Schonwerth collection. There are, of course, other books of collected folk tales, but if you go to any library or bookstore, you'll find the majority of writings on the Grimms, a little on Andersen and Perrault, virtually nothing on the French salon writers or earlier Italian writers, and very few collections of lesser known tales. To the right you can follow my tags for African, Native American, European, or Asian folklore, but there are relatively few of those compared to information about the Grimms or standard tales. Again, I can only read what's available on the internet, libraries, or reasonably priced books on Amazon-and I do try to keep in mind what readers might find most interesting. Psychologically, people will be more motivated to learn, and more likely to remember, something they already have a mental framework for; that's partly why artists and authors return again and again to the same, standard set of fairy tales.

Plus, it's helpful to have a common frame of reference. You could pull two stories which are technically Cinderella variants but have little in common; it would be very hard to have discussions without forming some sort of "standard" versions that are well known, as long as we avoid calling the Grimms' stories "the originals."

Edmund Dulac

Clearly, there's danger in remaining ignorant about fairy tales and their sources, but Dundes uses some pretty strong, opinionated language to describe people who only use standard literary collections as their source-they are "deluded individuals who erroneously believe they are studying fairy tales when they limit themselves to the Grimm or Perrault versions of tales."

The fact is, one of the great things about fairy tales is that they belong to the People. The tales told by peasants around a fire or over household chores are the true folklore. Yet, although the Grimms obviously changed their tales, Dundes also acknowledges that folk tales come in hundreds of variations; no two tellers would give word-for-word the same version of a story. So, among oral tellers and literary writers, change is an integral part of these stories. Just as the Grimms altered their versions to suit their audience, the people who told the stories to them had also changed the stories according to what they remembered, their own personal preferences, and their audience. In fact, those tales that he lauds as true folklore (that were told to the Grimms) were very influenced by the literary tales of Perrault, which had become well known and spread around Europe by the time the Grimms collected their stories, and many of the tales are likely descended from those literary tales.

Going further back, the tales of Perrault had been told and retold but many of them originated in the literary sources of the Italian writers, Straparola and Basile. (Read more on these Italian writers' influence on fairy tales from Ruth Bottigheimer's theory about the origin of fairy tales). Those stories were influenced by other literary works, and some motifs can be traced back to mythology, which we only know because many myths were written down. It gets very sticky to say that no written tales are true fairy tales, and that oral tales are "better" or "more authentic." There is no clear source, but we know fairy tales have a pattern of being shaped by writers, then the public, then back to writers, in a continuing cycle.

Still, it's important to remember that there is a whole world of fairy tales beyond the Grimms and Perrault (and Disney for that matter), and the variants that were told orally can be surprising to those who only know the most famous fairy tale versions.

No comments:

Post a Comment