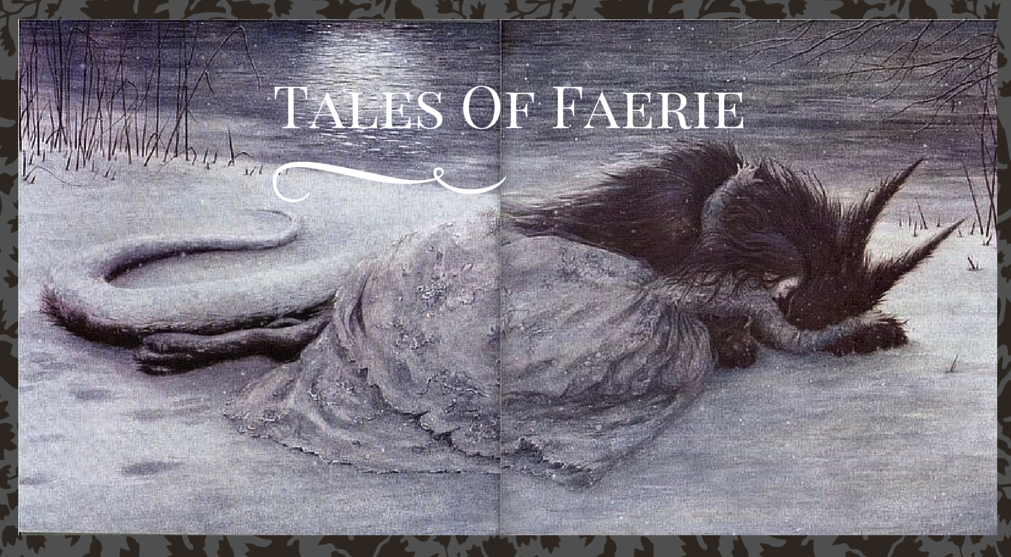

Image from this post at Once Upon a Blog

"The Little Sea Maid" is a fairy tale written by Hans Christian Andersen. Though inspired by mermaid folklore, it is an original story, not a reworking of oral tales.

"The Little Sea Maid" is a fairy tale written by Hans Christian Andersen. Though inspired by mermaid folklore, it is an original story, not a reworking of oral tales.

http://www.surlalunefairytales.com/ has an annotated version of the full tale.

I'm trying not to start every post by comparing a fairy tale to the Disney version, but Disney is so prevalent in our culture's thinking about fairy tales as well as my own personal knowledge of fairy tales, so it's hard to avoid. So, Ariel is officially my least favorite Disney princess (aside from Pocahontas, who doesn't even count. I have a friend who wasn't allowed to watch Pocahontas or Anastasia as a kid because they were historically inaccurate, which I find simultaneously sad and awesome).

The Disney version comes across as saying: a) don't listen to your parents, they're old and narrow-minded and don't know what they're talking about. b) not only is love at first sight true, but you should risk everything--including your safety, your future, and your family, to pursue your first crush.

The Disney version comes across as saying: a) don't listen to your parents, they're old and narrow-minded and don't know what they're talking about. b) not only is love at first sight true, but you should risk everything--including your safety, your future, and your family, to pursue your first crush.

The Andersen version starts very similarly, with the Little Sea Maid growing lovesick over a human prince, and eventually seeking the Sea Witch to give her legs. But not only must she give up her voice, but entered into a state of constant pain ("every step you take will be as if you trod upon sharp knives, and as if your blood must flow") and give up all chances of being a mermaid or seeing her family again. She is expected to woo the prince with her "beautiful form...graceful walk, and speaking eyes." And she doesn't succeed. The Prince isn't put under an evil spell to fall in love with the witch in disguise, but some other nice and pretty Princess. Given the chance to kill the Prince to save her own life, she declines. In the end she jumps into the sea, becomes sea foam, and then joins the "daughters of the air."

Critics have pointed out that this is more of a reward for her steadfastness than a punishment, since she enters into the afterlife, but I never read it that way (even though I do believe in the afterlife). Yet I find this ending much more satisfying than the stereotypical happy ending. She made a stupid decision as a young girl and paid for it, yet there is a glimmer of hope. It may seem that, after a broken relationship, there's nothing to live for any more, but life does go on, even if it can never be quite the same as it was before. I take the fairy tale as a message against becoming passionately attatched to someone prematurely.

.jpg)

Which is interesting, because at the beginning of the story, when the Sea Maid reaches her fifteenth year and is finally allowed to go above the surface of the sea, oysters are attatched to the Princess' tail, to show her high rank. The Sea Maid protested, "But that hurts so!" but the reply is, "Yes, pride must suffer pain." Later, the Sea Maid endures much more pain because of her love for a human. I don't know if I would call lovesickness "pride," per se, hers is more foolishness than anything else, or the fact that she was forced to wear oysters, for that matter. Andersen had his own moral agenda, which Maria Tatar elaborates on more in this book.

.jpg)

Which is interesting, because at the beginning of the story, when the Sea Maid reaches her fifteenth year and is finally allowed to go above the surface of the sea, oysters are attatched to the Princess' tail, to show her high rank. The Sea Maid protested, "But that hurts so!" but the reply is, "Yes, pride must suffer pain." Later, the Sea Maid endures much more pain because of her love for a human. I don't know if I would call lovesickness "pride," per se, hers is more foolishness than anything else, or the fact that she was forced to wear oysters, for that matter. Andersen had his own moral agenda, which Maria Tatar elaborates on more in this book.

To be honest, I think the main reason Ariel is so popular among little girls today is because she is a mermaid, and mermaids are cool, not so much because of her story. Lore about sea maidens generally tells a very different story--sirens who lure men to their deaths, or women kidnapped and forced to marry mortal men, but who escape as soon as they recover their seal skins. Mermaids have been made innocent and harmless much like fairies have.

No comments:

Post a Comment